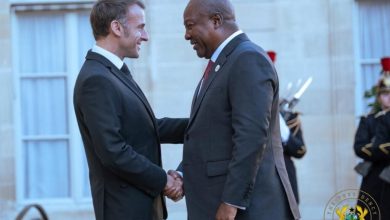

Yet the adversarial tone isn’t shared by Mahama, who says “the Chinese government has been supportive” of law enforcement efforts. “I don’t like to focus on just China.” And the fact that Washington is quite clearly preoccupied with Beijing renders the new U.S. posture “surprising,” says Mahama. “I can understand U.S. insecurity when it comes to China … but that’s when you need your allies. That’s when you need Canada, that’s when you need Mexico, that’s when you need the E.U. But if you are threatening the E.U. and all others with 50% tariff increases, South American countries with 100% tariff increases, you can’t tell the objective of this whole policy. Collaboration would have been better than the current global tensions.”

Washington’s efforts to paint China as the bad guy are undermined by the clear perception that American engagement is now rooted in interests rather than values. Still, while China has been ramping up its overseas investment, especially through its $1 trillion Belt and Road Initiative—a trade and infrastructure network spanning the globe—there’s little chance it will (or even wants to) replace U.S. wholesale.

While Beijing is laser-focused on ports, pipelines, and railways, the type of capacity-building engagement long characterised by USAID isn’t part of their strategy. China won’t fund projects promoting gender equity, affirmative action, training impartial judges, or improvements on regulatory performance in African nations, as these are not things that its government values at home.

Although self-reliance is Africa’s goal, the challenge is achieving true autonomy without structural transformation of nations that remain highly unproductive. Every country around the planet that has achieved structural transformation—from the Asian Tigers to the Balkans—has relied on large injections of foreign capital. Because when the status quo in sub-Saharan Africa is so unsatisfactory—with substandard education, healthcare, security, and so on—these tend to be the focus of domestic resources. Consequently, the bulk of future-focused projects are funded by donor agencies: green transition, incorporating AI, youth leadership, and media literacy.

In Ghana, for instance, USAID was a big investor in eco-tourism—attracting foreign visitors to nature sites to provide alternative livelihoods, so people will move away from illegal mining. “So even though the overall amount of aid is small, when you remove it, you create a very big gap in that future-rented segment of the country’s structural transformation,” says Simons of IMANI. “The future does not often appear as essential because we are so focused on the present. But the present cannot take us anywhere.”

The issue is how to inject capital without falling prey to some of the pitfalls of aid dependency. With commodity prices at record highs, Africa’s natural resource endowments are among the first areas to receive attention. And freed from the client-benefactor relationship that aid engenders, African nations are insisting upon local processing and refining to retain more of the downstream benefits.

“One thing we’d better get away from is this paternalistic attitude,” Khan says. “The ‘helping hand’ is a better approach, because people are then able to trade.”

For decades, the largesse of Western nations put their African counterparts in an awkward predicament, where they must “play polite” while the sovereignty of their resources is diluted, says Marcus Courage, CEO of Africa Practice, a business consultancy. “Now, African governments have recognised that they have more autonomy and must use it to become more self-reliant and to achieve genuine financial sovereignty.”

Guinea, the world’s top bauxite exporter, has begun mandating that foreign mining companies invest in local alumina refineries to increase value. Non-compliant firms, such as Emirates Global Aluminium, have seen licenses withdrawn. In Ghana, the nation’s first commercial gold refinery opened in August 2024, and Mahama launched a new regulator, GoldBod, to crack down on smuggling and boost state revenues. Gold exports have increased 75% year-on-year as a result. “It means that Ghana is able to get more from its gold resources,” says Mahama.

Technology can also help Africa unleash its hidden potential. The continent is home to 60% of the planet’s uncultivated arable land that is capable of sequestering immense amounts of carbon, yet only 16% of the global carbon credits market. This presents an untapped opportunity for African nations to monetise their mature forests and pristine wetlands, which are particularly prized for carbon capture. Opportunities also abound to sell credits for switching from fossil fuel stoves—some 80% of sub-Saharan Africans use wood or charcoal for cooking—to solar or biomass.

So far, Kenya, Gabon, and Tanzania have been first movers, with nations like Ghana, Uganda, and Zambia trying to catch up. The Congo Basin rainforest, for one, removes carbon from the atmosphere with a value of $55 billion per year, according to the Centre for Global Development (CGD), or equivalent to 36% of the GDP of the six countries that host the forest. “This asset can and should be seen as akin to mineral or oil deposits that have significant benefits for the countries that host them,” argues the CGD in a 2022 report.

Ghana has 288 forest reserves of which 44 have been invaded by illegal gold miners. “We’ve been able to liberate nine of them,” says Mahama. “And we have a program for starting a reclamation of those forest reserves to restore them.”

But it’s not just carbon. While the world gushes over Africa’s natural resources, trouble brews with utilising them—pollution, corruption, human rights abuses, and criminal infiltration. But what if there was a way to leverage such resources while they remained undisturbed? The global tokenisation of illiquid assets—everything from vintage paintings or vinyl records to collectors’ cards or real estate—is slated to become a $16 trillion business opportunity by 2030, according to the Boston Consulting Group. There is a growing clamour to use blockchain technology to tokenise commodities such as Ghana’s gold reserves, Botswana’s diamond reserves, and Zimbabwe’s platinum.

But while more efficient monetisation of natural resources would provide a shot in the arm, the crux is leveraging that windfall to diversify the economy beyond extractive industries—futureproofing economies for when commodity prices drop.

Mahama wants Ghana to move past mining and agriculture into processing and agribusiness, including foods and beverages, refined vegetable cooking oils and things like that. “We’re looking at digital services, fintechs, textiles, manufacturing,” he says.

For Mahama, Africa should not just seek to export to developed states but instead trade with itself. He cites the 2018 creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area—the world’s largest free-trade area, comprising a $3 trillion market—as an underutilised opportunity. In July, Narendra Modi came to Accra on his first visit by an Indian Prime Minister for three decades, and Mahama says the two leaders discussed sharing technology to boost Ghana’s budding pharmaceutical sector. “Already, we export [pharmaceuticals] in limited ways to our West African neighbours,” says Mahama. “But the African Continental Free Trade Area expands us beyond our 34 million population market to a 1.3 billion market.”

Of course, all this potential requires investment to realise. And while the drying up of no-strings aid money may well prove beneficial in the long term, the lack of alternative finance remains a problem. While self-financing is the ultimate goal, it will be a long road. African nations collectively possess only 20 sovereign wealth funds with a capitalisation of $97.3 billion—less than 1% of the global total.

Compounding issues, many African countries pay four times more interest on their debt than high-income nations, despite often having lower debt-to-GDP ratios. As a result, an average African government spends 18% of all state revenue on interest alone, according to the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI), compared to 3% for E.U. nations.

The TBI has proposed a new cost-efficient $100 billion debt-swap facility administered by multilateral development banks to essentially consolidate and refinance existing liabilities at concessional rates. Kenya, for one, is servicing an international loan of $1.5 billion at 9.5% interest. Refinancing at 3% would save $97.5 million annually.

Of course, $97.5 million is a colossal amount that could be used to fund schools, hospitals, and key infrastructure. Still, it is less than half the $225 million Kenya was due to receive from USAID, of which half in turn was due to be spent on healthcare. The U.S. is not the only country to slash aid—the U.K. is cutting its aid spending from 0.7% of GDP pre-pandemic to 0.3% by 2027—though the manner in USAID was atomised, combined with steep tariffs, still leaves a nasty taste for Mahama.

“Since the end of the Second World War, we’ve had a world that has been more interdependent and has dealt with international relations in a multilateral fashion,” he says. “Things are changing now. It looks like unilateralism has become the order. But it does not help anybody because the world progresses together.”

Source:FiilaFmonline/Joynews