Life StyleNews

Full Statement: After 1yr, ‘Corruption Watch’ assesses work of Special Prosecutor

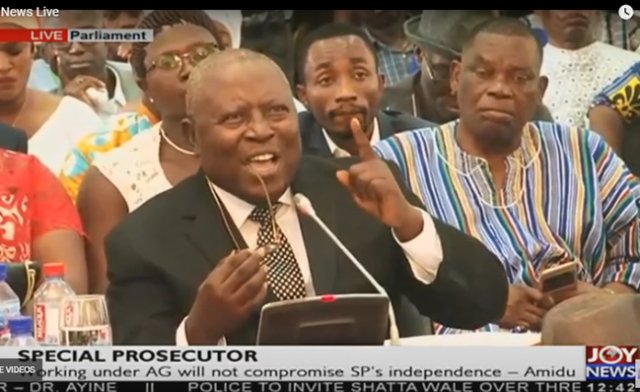

Corruption Watch and Democratic Institutions and Systems Strengthening (ADISS) have presented an assessment of the Office of the Special Prosecutor headed by Martin Amidu, after one year in office.

This follows public outcry about the slow pace of work which has enmeshed the office.

Speaking Monday, at a press briefing sponsored by STAR-Ghana and ADISS, Director of Advocacy and Policy Engagement at the Centre for Democratic Development (CDD), Kojo P. Asante, made a number of recommendations including tooling the Office of Special Prosecutor adequately, to better discharge its mandate.

“Without a bigger place, new officers would not have a workings space. However, the processes of recruitment can start, in anticipation of the office being ready. This means the President must exercise his discretion to delegate the power of appointment of Staff to the Board or the Special Prosecutor himself as quickly as possible,” he said

The full statement is reproduced below.

Introduction

In December 2017, the Parliament of Ghana passed the Office ofthe Special Prosecutor (OSP) Bill 2017 into law.

It was only after undergoing more than thirty amendments that this Bill was finally passed, having been laid before the House in July 20171.

The passage of the OSP Bill demonstrated President Akufo-Addo administration’s will to create a specialized agency, capable of investigating and prosecuting corruption cases concerning political exposed persons and recovering monies stolen for the State.

Prior to the laying of the Bill and throughout the work of the Parliamentary Committee on Constitutional, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs, the key contentions were first, how this new entity could function independently from the Attorney General to tackle corruption without fear or favour and second, whether the new entity was likely to duplicate the work of other anti-corruption institutions already struggling for resources.

A lot of ‘legal engineering’ was employed to try to respond to these contentious issues.

Anti-Corruption Civil Society Organisations (CSO), persuaded by the rationale for a single purpose anti-corruption body, played a critical role in improving the Bill substantively before passage.

Subsequently, the CSOs that supported the passage of the OSP law mobilised under a loose coalition to monitor the implementation of the law, following its passage.

It is under this context that we are gathered here today.

Over a year since the OSP was established, it is time to assess progress made or how to overcome challenges, if they exist. Let me thank STAR-Ghana and Accountable Democratic Institutions and System Strengthening (ADISS) project for making this event possible.

Let also thank our partners Multimedia (Joy FM and Joy TV) as well as Citi FM.

I present this report on behalf of Corruption Watch, the CSO Coalition on the OSP and ADISS.

This report assesses the OSP along five key dimensions: Appointment of key officers of the Office in terms of compliance with the spirit and letter of the law; Setting up of the Office including infrastructure, staffing, logistics and financing; Operationalization – looking at the core mandate to the Office to investigate, prosecute and recover stolen resources; coordination and collaboration with sister agencies; and public engagement.

In assessing these areas, I will look at the expectations of the OSP Act 2017 for each of the key dimensions, what has been observed during the period under review, and propose ways to close the gaps if there are any.

1. Appointment of Key Officers

The OSP Act, 2017 (Act 959) provides for the appointment of a Special Prosecutor, a Deputy Special Prosecutor and the constitution of a Governing Board to manage the affairs of the Office. The procedure for appointing these officers and the Board were carefully designed to ensure the independence of the Special Prosecutor and the Deputy but also consistent with the tenets of Article 88 of the 1992 Constitution which grants exclusive prosecutorial powers to the Attorney General.

Section 13(3) of Act 959 gives the Attorney General the power nominates for the President to appoint subject to the approval of a majority of all Members of Parliament.

Entrusting the power of nomination in the hands of the AG is also consistent with Article 88(4) which allows the AG to delegate her exclusive powers to prosecute.

On the 31 st January, 2018, the media reported widely that the ‘President had nominated Mr. Martin A.B.K. Amidu’ as Special Prosecutor subject to parliamentary approval.’

Certainly, if it was the case that the President had nominated Mr. Amidu, it would have been an illegal procedure.

Thankfully, the actual statement from the Jubilee House, did state that the President had accepted the nomination of Mr. Amidu after the Attorney General Ms. Gloria Akuffo had exercised her power of nomination and submitted Mr. Amidu’s name to him.

As such, the nomination was done according to law. The only minor action we must reconsider for the future is whether or not the announcement of the nominee should be done by the AG or the President. We cannot fault the President to want to claim the adulation, this being the first time. But we must always be reminded of both the appearance and substance of independence in the eyes of the public.

This is critical to building the character of the office from the very beginning.

Mr. Amidu was then vetted by Parliament’s Appointments Committee, recommended for approval and unanimously passed by the House.

On 23 rd February 2018, he was sworn in by President Akufo-Addo to begin his seven-year term.

The Deputy Special Prosecutor, Ms. Jane Cynthia Naa Korshie Lamptey went through the same process in April and May 2018, and was sworn in end of May. It is important to note that despite the careful design of the nomination and appointment procedure, it was a real surprise to everyone that Mr. Amidu was chosen as Special Prosecutor.

Even the most optimistic activist could not have imagined that a sitting President will appoint a leading member of the largest opposition party to the post. But it is also the case that one can describe Mr. Amidu as being more than a party member but committed public servant, principled and an anti-corruption campaigner. So the President should be commended for his choice.

In our humble opinion, these legal guidelines for nominations and appointments represent the floor and not the ceiling as to what can be done; those who have responsibilities can go above and beyond the floor to fulfill the spirit of the law.

Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, another key set of officers that needed to be appointed were the Governing Board.

Section 5 of Act 959 provides for a Board consisting of:

(a) The Special Prosecutor;

(b) The Deputy Special Prosecutor;

(c) One senior representative from the following institutions:

1. The Audit Service (Director nominated by Auditor General)

2. The Ghana Police Service (ACP and above nominated by IGP)

3. The Economic and Organised Crime Office (Director nominated by ED)

4. The Financial Intelligence Centre (Director nominated by ED)

5. The Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (Director, nominated by

ED)

6. An individual with a background in intelligence (Director, nominated by Minister

responsible for National Security)

7. A female representing the Anti-Corruption Civil Society Organisations.

Section 6 of Act 959 stipulates the Board’s duties which include: policy development; ensuring effectiveness of the Office; advising on the appointment of the Administrative Secretary and other senior officers of the Office; promoting cooperation between the Office and relevant national investigative bodies and developing and monitoring the implementation of a code of conduct for staff of the Office. In addition, the Board should not interfere in the day-to-day functions of the Office.

The structure of the governing board was carefully debated during the Parliamentary Committee deliberations because of the experience of governing boards engaging in ‘mission creep.’ Particularly, this was a case where the Office was being set up to make independent decisions to investigate and prosecute; any interference in those functions would undermine the rationale for setting it up.

This is why a coordinating board was envisaged to assist the Office to carry out its mandate.

Though delayed, in July 2018, the President inaugurated the OSP Board, almost five months after Mr. Amidu took office.

Per the OSP law, the Board elects its own chair. Mrs. Linda Ofori-Kwafo, Executive Director of the Ghana Integrity Initiative (GII) was elected Chair of the OSP Board. Board Members are to serve a three-year term renewable once.

The constitution of the Board was a key component to activating various provisions of the Act. For example, the Board was expected to advise on the appointment of an Administrative Secretary and without a Board in place that could not happen. Also, the Administrative Secretary is expected to arrange the meetings of the Board.

As such until the Administrative Secretary was appointed Board meetings were delayed.

Though the Board was constituted late and held its first board meeting a month later in August 2018, it was able to support the Special Prosecutor to address some of its immediate needs which included the appointment of an Administrative Secretary to run the office and consult on the passage of a Legislative Instrument for the OSP Act that has been outstanding since March 2018.

Subsequently, the Board continues to work with the Special Prosecutor to secure a bigger permanent office. Certainly, there are many things to prioritise at this stage and some of the Board’s responsibility may have to be put on hold.

Nonetheless, the Board should seriously consider the development of a medium-term strategic plan that will document the plans and activities for the office in the next 3-5 years to provide a framework for those who want to support the office over the medium term. Not only does this ensure continuity at this early stage of the establishment of the office but provides a framework for those who want to support the office.

2. Setting up the Office of the Special Prosecutor

Section 19 of ACT 959 gives the reader a scope of the task of the OSP. The OSP is expected to have four divisions: Investigations; Prosecution; Asset Recovery and Management; Finance and Administration.

The Board has the power to establish more divisions. A Secretariat is also to be established and headed by the Administrative Secretary.

The Administrative Secretary is responsible for the day-to-day running of the office and answerable to the Special Prosecutor. The provision of a Secretary was to ensure that the OSP was freed up to focus on the core business of investigations, prosecutions and asset recovery and management.

This was to address another Ghanaian public sector institutional culture where operational heads are tied up or attracted to day-to-day secretarial duties instead of core business. Other safeguards were provided to ensure the substantive independence of the OSP.

These include the requirement for OSP to make a request before an officer can be transferred or seconded to the Office. All other staff are still expected to be appointed by the President in accordance with Article 195 of the Constitution. However, the President may delegate that power of appointment to the Board or a public officer.

Upon their appointment, Mr. Amidu, his Deputy and a private secretary were housed in a former three-bedroom house in Accra. Once Mr. Amidu, his deputy and private secretary took up offices the only place left was a room downstairs which was converted into a conference room. Subsequently, the Special Prosecutor secured some additional staff including the administrative secretary and then three investigators seconded from the Police Service.

There was no room to house the officers so the boys’ quarters was converted to accommodate them. Seven months after his appointment, the situation had not changed, causing the Special Prosecutor to voice out his frustration at a National Audit Forum organised by the Ghana Audit Service in September 2018.

There the Special Prosecutor complained about the lack of a Legislative Instrument (LI) to guide his operations and the logistics to aid his work.

Then on 8th November 2018, he issued one of his epistles. In that article, he compared

his situation to a ‘Whitaker Scenario’, a scenario outlined by the then President Trump’s Acting Attorney General, Matthew Whitaker, where he had envisaged a scenario where Special Prosecutor Robert Muller who was conducting a probe into Russia meddling in US Elections could be underfunded to an extent the probe would come to a halt.

CSOs and media took up the matter and called on government to resource the office. CSOs even visited the premises of the OSP to see for themselves the nature of the problem. Government’s machinery began to work in September 2018 as various building options were proposed, including one next to the International Press Center which was deemed unsuitable. The positive news is that now we understand a large building has been identified and agreeable to the Special Prosecutor.

The OSP and the Office of the Chief of Staff are working to ensure proper handover of the building.

Also in November 2018 two Legislative Instruments – Office of the Special Prosecutor Regulations, 2018 and Office of the Special Prosecutor (Operations) Regulations 2018 – were laid before Parliament and passed after 21 sitting days.

The general regulation was to elaborate on the powers of the SP in relations to its core mandate and the regulation of the operation was to address the general management of the Office.

Financing the Office of the Special Prosecutor

Another issue that had been raised by the Special Prosecutor was the matter of funding. Some allocation had been made in the 2018 budget of the Attorney General but the delays in addressing the set up of some basic structures had meant that the money could not be utilised.

In the 2019 budget, read in November 2018 by the Finance Minister, the OSP was allocated GHS GH¢180,160,231.

The breakdown is as follows:

a. GH¢88,013,859 for goods and services

b. GH¢58,675,906 for capital expenditure including the acquisition of a purpose-built office facility, outfitting and procurement of special general purpose vehicles, office furniture, computers, modern security and communication equipment, among others

c. GH¢33,470,466 for compensation to recruit 249 new crops of staff as part of the measures to fully operationalise the Office.

There was an error in the schedule presented to Parliament that indicated that the OSP had been given a ceiling of 12 staff. This was later corrected when Parliament queried the Finance Ministry during the budget hearings.

Apart from money from government, there has been significant development partner interest in supporting the Office right from the beginning. This also proved difficult because of section 22 of Act 959, which stipulates that all grants have to be approved by the Minister of Finance in consultation with the Attorney General.

This meant that Minister of Finance needed to set out modalities on how the OSP can receive funds. After a little merry-go round that is now addressed. All grants to the OSP are handled as normal grants between the Government of Ghana and Development Partners through the External Resource Mobilisation Divisions (Bilateral and Multilateral).

The Finance Ministry, however, still needs to issue a direction note on how it will process such assistance.

A quick commentary on our observations relating to the setting up of the office so far.

In our respectful opinion, government initially underestimated the scope of the task ahead in setting up the office.

The OSP, for example has police powers and in that regard when he arrests or detain a suspect, he should have the requisite logistics, the appropriate holding vehicle, interrogation rooms and equipment to conduct investigations.

Thus, in spite of the huge amount allocated to OSP for 2019, recruitment cannot be expedited without an office to house the personnel.

This means securing the Office is critical to speeding up the operationalisation of the OSP. It is our hope that both the OSP and government can find a quicker solution to the handing over of the office.

Also, to speed up the process of recruitment, we would also like to take this opportunity to respectfully request that the President formally and urgently exercise his discretion to delegate his power of appointment of staff under Article 195 (2) of the Constitution. Per 195(2), he can delegate that power to the Governing or even to the OSP.

A delegation can speed up the process of recruitment and further enhance the independence of the Office.

Lastly, in relation to the Board, it is important to remind the OSP that all Board Members and Staff are expected to declare their assets and liabilities in accordance with Article 286 of the Constitution.

If it has not been done, it should be. The Auditor General has a very user-friendly online version of the form now and they should take advantage of it.

Investigations, Prosecution and Asset Recovery and Management Two provision are important in respect of this dimension of the assessment. Section 6(2) of Act 959 stipulates that the Board shall not interfere in the day-to-day functions of the Office.

Then, Section 14 states that the Special Prosecutor is accountable to the Board for the performance of his duties but retains full authority and control over investigations, initiations and conduct of proceedings regarding the functions of the Office. So, it is the SP’s sole responsibility to initiate investigations into cases, receive and act on referrals from CHRAJ, EOCO, Auditor General, any other public office.

Critical to activating all these power and actions is having protocols in place to receive and investigate complaints of corruption and corruption related offences. We need to remember that most of these actions just described could not have happened without clear rules on how the OSP was going to exercise those powers granted under the Act.

Those rules were to be elaborated in the LI. Therefore, the delay in the passage of the LI did not help. Not having a building fit for purpose did not help, but at the same time the long drawn out bureaucracy in putting these structures in place has also not helped.

Notwithstanding these delays let us assess what has been done so far in this area.

Mr. Amidu has stated on several occasions that he does not want to comment on individual cases because of the rights of the individuals involved. Everyone is innocent until proven guilty and so it is important their reputations are not damaged before they are charged with a crime.

Taking that into consideration, we have highlighted only cases where the complaint had indicated publicly that they had lodged a complaint or cases the Special Prosecutor had publicly commented on. In essence, the knowledge of these cases are a matter of public record. In all, we counted about eight cases, but we know there are higher numbers being banded around.

BOST: In early 2018, the CEO of Chamber of Petroleum Consumers [COPEC], Duncan Amoah,

petitioned the Special Prosecutor, Mr. Martin ABK Amidu on a case involving financial loss of an

estimated GHȻ 30 million to the state at BOST. COPEC alleges that BOST decided to sell 1.8 million barrels of contaminated fuel to BB Energy2. The Special Prosecutor acknowledged receipt3.

Metro Mass: Some workers of Metro Mass Transport, led by Mr Fusseini Lawal Laah (the Head of Security of MMT) petitioned the Special Prosecutor to investigate Mr. Bennet Aboagye (former Managing Director of the MMT) over procurement malpractices4 in the award of a contract for the purchase of about 300 new buses and electrical products from Ankai Company.

Again, Mr Aboagye was alleged to have been receiving full salary and allowances though he had been interdicted by the President and a substantive MD had been appointed. Mr. Aboagye admitted to the payment of GHȻ 40, 000 bribe to Mr. Lawal to retrieve an alleged recording implicating him, but claims the money was extorted from him.

Office Special Prosecutor responded to the petition and indicated that his Office will investigate the allegations once it starts work.

o CHRAJ is collaborating with the OSP in prosecuting this case. The Commissioner, Mr. Joseph

Whital, has indicated that the Commission is waiting on the OSP to provide them with TOR to

start their investigations – since petitioners petitioned both offices and parallel investigations will

not be helpful. I will return to this case shortly.

Anas galamsey: Anas and his team TigerEye PI formally petitioned the office of the Special Prosecutor to investigate a piece on alleged corruption/bribery case involving Mr. Charles Bissue, Presidential Staffer and Secretary to the Inter-Ministerial Committee on Illegal Mining.

o Mr. Martin Amidu confirmed receipt of the petition and promised that his office would investigate the matter. The OSP invited and has now interrogated Mr. Bissue5. Mr. Andy Owusu6 was also recently invited over their alleged involvement in corrupt acts.

o The Criminal Investigations department of the Ghana Police Service is conducting parallel

investigations into the issue but the level of collaboration with the OSP is not clear. [P.S] The

involvement of the CID in investigating Mr. Bissue has been described by Mr Kweku Baako, editor of New Crusading Guide, as surprising since the matter is pending before the OSP7. I will

return to this case as well.

Some 13 Ghanaians petitioned the office of the Special Prosecutor to investigate a report of alleged thievery of state resources by former appointees of then-President John Mahama, including Mr Kwadwo Twum-Boafo of the Freezones Board, Mr George Ben-Crenstsil of the Ghana Standards Authority, Mr Kingsley Kwame Awuah-Darko of BOST, Sedina A. Tamakloe of MASLOC, Kakra Essamuah of BOST, among others8.

Tax evasion- Honourable Mahama Ayariga: The Special Prosecutor is investigating Hon. Mahama Ayariga for abusing his public office for private gains. The case involves the importation into Ghana through alleged corrupt means and corruption-related activities of three used white Toyota Land Cruiser V8 vehicles9.

o The Special Prosecutor indicated that he invited the Economic and Organised Crime Office to

undertake a joint investigation of the suspected offences in accordance with the law. The Special Prosecutor also stated that he has reported the Bawku Central MP to the Economic and Organized Crime Organization (EOCO) for attempting to obstruct him10.

Double salary allegations: 8 persons out of a total of 25 initially invited by the CID have been

interrogated by the CID over allegations of having received double salaries as MPs and ministers 11.

o Mr. Amidu expressed worry over the case and indicated his support for the CID in investigating the matter. It is not clear whether his office has been petitioned on the matter.

A group known as the Strategic Energy Forum petitioned the Special Prosecutor to investigate alleged procurement breaches and conflict of interest against the Chief Executive Officer of the Ghana National Petroleum Cooperation (GNPC), Dr. K.K. Sarpong12.

Ghost names on government payroll: The Auditor General is collaborating with the OSP to prosecute public servants who are found in payroll malfeasance.

o The Special Prosecutor confirmed the collaboration and indicated the willingness of his office to take on corruption cases emanating from audit reports13. It is not clear whether cases have been referred to the OSP.

So, at least we can say with some confidence that some investigations have taken place and at least in one case charges have been filed in Court.

I think the work done so far has to be placed in the context of the performance of other agencies in the sector.

During the reading of the 2019 budget statement, we were informed that the AG received 266 criminal cases from the police and prosecuted 226. We don’t know how many cases were investigated and we don’t know how many cases were corruption cases.

The AG has about 89 prosecutors and an additional 50 were recruited to add to the

number. This is still woefully inadequate but at least efforts are being made in the right direction. In the case of EOCO, we were told that 466 cases were investigated, 34 were prosecuted, with two convictions secured and GHS 7.5 retrieved (2019 Budget Statement – pages 179-180).

The general picture needs to be improved substantially to ensure optimum use of resources. But this means with the constraints outlined so far in relation to the OSP, there is progress even though we expected the OSP to buck the trend of existing law enforcement in the near future.

Coordination and Collaboration with other Institutions Section 73 of Act 959 states that the Office may work together with other institutions.

All public officers are under an obligation to cooperate with the Office. An officer who refuses or fails to cooperate without reasonable cause commits an offence and can be fined or go to jail. Also under Section 28, the Office can request for information from public officers and if the officer refuses, conceals or fails to comply without reasonable cause, he or she commits an offence under the Act. Thus there is no shortage of powers for the Office to compel cooperation.

However, Parliament understood that it was preferable not to use these powers in the first instance but rather cultivate an environment of cooperation. It was for this purpose that the composition of the governing board of the OSP consists of institutions the OSP would ordinarily work with.

The frequent interaction with the Office at the highest level is supposed to build trust and cooperation. However, under the period of review it is clear that this has not been smooth sailing.

The cases highlighted earlier shows that the OSP has tried to use the cooperation approach to kick start investigations for some of the cases. Examples are with the Tax Evasion case with EOCO, Ghost Names cases with the Auditor General and the Metro Mass Transit case with CHRAJ. Certainly, depending on whose investigators you are using for any of these cases, it is likely the OSP does not have full control of the case particularly in a command and control setting like law enforcement.

However, it appears in the Metro Mass case the matter was handled effectively, at least in the case of CHRAJ. Though CHRAJ has an original mandate under the Constitution to investigate corrupt cases and had also been petitioned, it deferred to the OSP on the case and sought to collaborate with OSP. This has not happened in the cooperation with the CID, in both the Metro Mass and the Galamsey cases.

In the Metro Mass case, the compliant who took the case to the OSP ended up being investigated and prosecuted by the CID. In the Galamsey case, though Anas had announced that he had submitted the case to the OSP, the CID opened a case on the same matter upon the instructions of the Minister for Interior.

Apart from the obvious duplication and waste of resources, it can only encourage forum shopping on the part of the suspect.

ACT 959 is clear that corruption and corruption-related offences are the preserve of the OSP. These offences included offences listed in the Criminal Offence Act of 1960, procurement offences and related offences to the two categories.

During the Parliamentary Committee deliberations, there was an effort to insert a take over clause allowing the OSP the power to take over corruption cases started by other agencies if it so wished.

This was to affirm its jurisdiction. The only reference to this jurisdiction was expressed in Section 81, under transitional proceedings where the AG could exercise its discretion to pass on cases handled by the other agencies to the OSP.

Certainly the propriety of such a decision by the Attorney General would depend on the capacity of the OSP to handle such cases.

But surely, it should be clear when a new matter on corruption has been reported to the OSP and he is dealing with it, there is no need to open another case at a different agency. The governing board was designed to deal with such matters and should be called upon to address it. But going forward, the OSP require a cooperation, coordination and collaboration protocol agreed with other agencies that would guide everybody when these overlaps emerge. This is a policy matter the Board must take up.

Public Engagements

The OSP law requires publication ofcertain pieces of information every half year. These include list of corruption cases investigated and prosecuted, number of acquittals, convictions and cases pending in relation to prosecutions and the value of assets recovered. This should be published in two national dailies and on the website of the OSP.

As we have always maintained these guidelines are the minimum standards and the OSP can and should provide more information as relevant and appropriate. The general principle of the citizen right to know already exists as a constitutional right and, with the passage of the RTI law, should provide more encouragement to the OSP to share more.

The Chairperson of the Board of OSP has stated that the Office will discharge its responsibility to publish a half yearly report14. Also, the Special Prosecutor, Martin Amidu has stated that his office will prosecute its first case in 2019.

Speaking to Metro TV, Martin Amidu stated that his office has responded to all petitions sent to them and assured the public of their commitment to prosecute corrupt cases brought the OSP.

Thus we expect to have an official account of the activities of the Office for public record sometime in June. In addition, once an audit is completed, submitted to the Board and then to the Attorney General, she is supposed to lay it before Parliament, which means there would be another public record. These requirements are important for transparency and accountability and should be a model for all law enforcement agencies even without statutory compulsion.

Another aspect of the public engagement goes beyond sharing information, but also engaging with the public and accounting to the people so they can also play their role in supporting the office to fulfill its mandate.

That starts with the friendliness of the complaints procedure and accessibility. Given the constraints outlined it is understandable that there is still a lot to do in this area. For example, there is no website yet for the office to even provide for online complaints, and tips. Going forward, this will need to be expedited.

The public must have a user-friendly system for reaching out to the Office.

The OSP has also worked closely with CSOs. This is because CSOs played an important role in preparing the law establishing the Office and have also being a strong supporter of the Office. The OSP have met with CSOs in a number of occasions to share information on his work and challenges and CSOs have used its advocacy to try to get this matters addressed. Today’s event is further testimony to the interest we have in supporting this Office to work.

Conclusion

To conclude, pervasive corruption remains an existential threat to the stability and prosperity of our dear Republic.

President Akufo-Addo and the NPP’s proposal for a single purpose vehicle to deal with the problem, particularly as it relates to politically exposed persons, was appropriate in the circumstances.

The appointment of Mr. Amidu raised even more expectations amongst the citizenry of tackling corruption in a serious manner.

After a little over a year since the Office of the Special Prosecutor was established we have seen progress but it has not been fast enough to meet the expectations, some of which were admittedly unrealistic.

But if we have lost time at the beginning we should not lose more time now. As long as all stakeholders are committed we should be able to make up for lost time. From the assessment a few key issues have to be resolved as the OSP becomes fully perational.

1. The process of handing over the building for the OSP and refitting it must move quicker. All parties must act with speed.

2. Without a bigger place, new officers would not have a workings space. However, the processes of recruitment can start in anticipation of the office being ready. This means the President must exercise his discretion to delegate the power of appointment of Staff to the Board or the Special Prosecutor himself as quickly as possible.

3. There are a lot of cases that the OSP would have to deal with. This will take time – both investigation and prosecution if necessary. Though we have to be vigilant, we also have to remember the rights of the accused.

4. A Coordination, Cooperation and Collaboration protocol is needed urgently to manage overlapping mandate. But generally the OSP’s mandate is corruption and corruption-related offences and it is in order to give him first bite on these matter

5. We have to allow the OSP to fulfil its mandate in June 2019 to share information on its work. This exercise is one that CSO encourage all law enforcement to adopt even without legal obligations.

A website is also needed.

Lastly, it is a fact that independence is essential for the OSP and we must guard that jealously. However, it is also important for that to be balanced with transparency and accountability. It is this combination that would help the OSP succeed.

Thank you for your kind attention.

Source: Myjoyonline.com